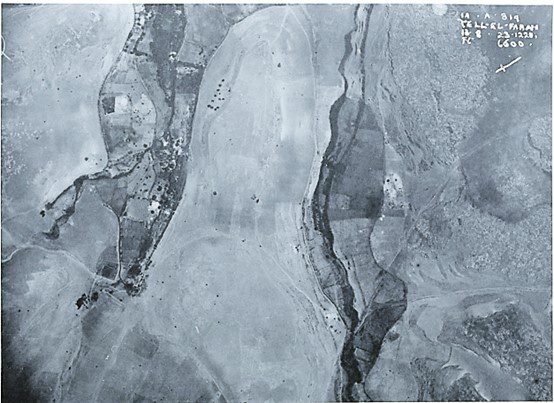

The city of Tirzah, identified with Tel al-Farah North, lies in the Samarian highlands between the modern cities of Nablus and Tubas. Positioned adjacent to two perennial springs, Ein Tirzah (Ein Farah) and Ein al-Bida, the site marks the beginning of the Tirzah stream valley, which meanders from the hill area towards the Jordan Valley in the east, facilitating convenient transportation. Tirzah stands among several pivotal settlements on the Samaria ridge, alongside Shechem and Samaria, both of which served as capitals of the Kingdom of Israel at different periods. In biblical tradition, Tirzah is the name of one of the youngest of Zelophehad’s Daughters.

As a city, it is counted among the Canaanite cities conquered by Joshua, briefly assuming the mantle of Israel’s capital for approximately 50 years. Song of Songs 6:4 refers to its beauty: “You are as beautiful as Tirzah, my darling, as lovely as Jerusalem“. Archaeological excavations at Tell el-Farah unearthed evidence of an urban settlement persisting intermittently from the Neolithic period through the end of the Iron Age. It is important to note that this site differs from Tel al-Farah South, located near the Besor Stream in the western Negev.

Research history

The association of Tel al-Farah with the biblical Tirzah, referenced 17 times in the Bible, was initially proposed by archaeologist William P. Albright in the 1930s. Despite initial debates regarding this identification, subsequent discoveries, including the Samaria Ostraca, along with archaeological findings at the site, lent credence to Albright’s assertion. The site underwent excavation during nine seasons spanning from 1946 to 1960, led by a delegation from the French School of Biblical and Archaeology in Jerusalem under the direction of Roland De Vaux. In 2017, excavations at the site recommenced as part of a collaborative endeavor involving A Coruña University from Spain, NOVA University from Portugal, and the Ministry of Tourism of the Palestinian Authority.

Early settlement at Tel al-Farah and the Canaanite period

The earliest traces at Tell al-Farah date back to the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic period (seventh millennium BC). Archaeological investigations have focused on numerous caves utilized for habitation and burial purposes during the Chalcolithic period and Early Bronze Age 1. The inception of the first city at Tell al-Farah occurred during the Early Bronze Age 2, revealing remnants such as a fortified wall, a city gate, residential structures, and a potter’s workshop.

By the 19th century BC, marking the onset of the Middle Bronze Age, a village had evolved, yielding several burial sites. In the 16th century BC, the city underwent redevelopment, featuring a new system of fortifications covering a smaller area than its predecessor. Adjacent to the city gate stands a building identified by De Vaux as a ritual site. During the Late Bronze Age, spanning from the 13th to the 16th centuries BC, a settlement flourished, though its exact extent proved challenging to ascertain during excavations.

Tirzah: Israel’s forgotten capital

The discoveries at Tell al-Farah from the Iron Age provide evidence of the political and economic prosperity enjoyed by the site during this epoch. Throughout this period, the city underwent multiple reconstructions, sparking lively debates among researchers regarding the significance of these findings. Dr. Assaf Kleiman’s historical reconstruction of the layers is informed by the renewed excavations at Tel Rehov and Megiddo. In the mid-10th century B.C., following the destruction of Shechem during the Iron Age 1, a settlement emerged at the site characterized by well-organized streets. Initially occupying a modest area of only 10 dunams without fortifications, this settlement gradually evolved into a significant urban center during the transition between the 10th and 9th centuries BC.

According to biblical accounts, Jeroboam I, the first king of Israel, relocated the capital from Shechem to Tirzah. The 9th century BC witnessed Tirzah embroiled in civil strife, with conflicts erupting between the kings of Israel. Basha murdered Nadav, Jeroboam’s son and ruled for 24 years at Tirzah. His son Elah is described as a drunkard and debauched, was murdered by Zimri, who ruled for seven days. He was then deposed by Omri, who fought for four years against Tibni and then assumed complete power over Tirzah. In the sixth year of his reign, Omri opted to relocate the capital of the Kingdom of Israel to a new site, establishing the royal compound in Samaria. Consequently, Tirzah lay in ruins for the remainder of the 9th century BC.

Tirzah under the Nismides and after the Assyrian conquest

In the 8th century BC, the city underwent reconstruction during the reign of the Nimside dynasty, yielding the best-preserved findings from the Iron Age. Archaeological evidence indicates the presence of public buildings and even a palace in the northern part of the city, while simpler residential structures dominated the southern sector. The sacred compound, dating back to the Middle Bronze Age, continued to host public and potentially ritual activities during this period. A “LMLK” jar-handle was found, inscribed with the words “to Shmaryo”, maybe a court official. Several tombs dating from the 7th – 8th century BC were uncovered around the mound. One of the last kings from Samaria to rule over Israel, Menachem, came from Tirzah: “Then Menahem son of Gadi went from Tirzah up to Samaria. He attacked Shallum son of Jabesh in Samaria, assassinated him and succeeded him as king” (2 Kings 15:14)

However, the city met its demise in 721 BC during the violent onslaught led by Sargon II. Following the destruction, remnants suggest a diminished settlement persisted, perhaps indicating Assyrian presence with finds resembling Assyrian style. By the 6th-5th centuries BC, the settlement dwindled and eventually was abandoned, marking the first phase in which the sacred complex fell into disuse. Subsequently, after Tel al-Farah was finally deserted, agricultural activity characterized the Roman period, while a Muslim cemetery was established on the site.

Sources:

De Vaux R. (1952) LA QUATRIÈME CAMPAGNE DE FOUILLES A TELL EL-FAR’AH, PRÈS NAPLOUSE. Revue Biblique.

Finkelstein, I. (2012). Tell El-Far’ah (tirzah) and the Early Days of the Northern Kingdom. Revue Biblique (1946-), 119(3), 331–346.

Jasmin, M. (1997). Tell el-Far’ah (N). In E. M. Meyers (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East.

Kleiman, A. (2018). Comments on the Archaeology and History of Tell el-Far’ah North (Biblical Tirzah) in the Iron IIA [Review of Comments on the Archaeology and History of Tell el-Far’ah North (Biblical Tirzah) in the Iron IIA]. Semitica, 60, 85–104.

Zertal A. 2004. The Manasseh Hill Country Survey, Volume I: The Shechem Syncline, Volume III.