Glossary

a'

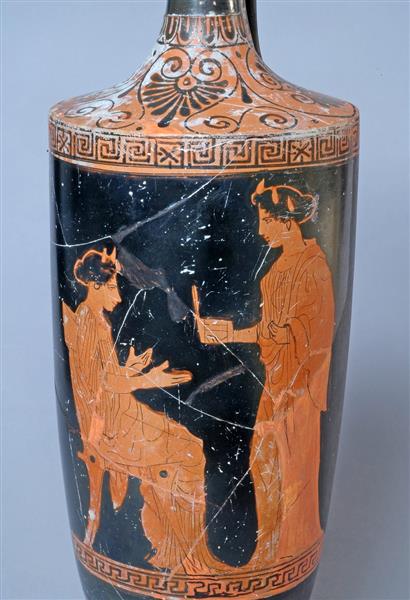

Attica is an ancient region in southeastern Greece and is currently one of the 13 administrative regions of modern Greece. According to the Roman geographer Pausanias, who lived in the 2nd century CE, Attica was named after Attis, the daughter of Cranaus, a mythological king of Athens. Products made in Attica and exported worldwide are known as ‘Attic products.’ Particularly notable are the Attic ceramics, renowned for their exceptional quality and exquisite decoration, which were widely used during the 6th-4th centuries BCE (Persian period). Attic pottery was exported throughout the ancient Near East.

There are two main types of decorations on Attic pottery:

- Black-Figure Technique: This older technique features red pots with black-painted figures, often with additional details in white.

- Red-Figure Technique: This later technique involves painting the pots black and leaving spaces unpainted to form red figures, with further details added in black.

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/place/Attica-ancient-district-Greece

https://anticopedie.fr/mondes/mondes-gb/attique-ceramique.html

Coins are (usually) round pieces of metal that are used as an agreed upon means of payment in the buying and selling of goods and services. The first coins were minted about 2,600 years ago and since then have played an important role in the development of human civilization. On top of the coins are usually figures of rulers and their names, dates and ethnic and religious symbols. In archaeology, coins are used as a central tool for dating and research resulting from circulation and deciphering the messages imprinted on them. Before the appearance of the coin, precious metals were used as a common means of payment as ingots, jewelry and silverware, and sometimes bore a stamp indicating their origin. The invention has significantly improved trade.

The first known coin was called “Electrum”, it originated in the late 7th century BC in the Greek city of Lydia. The coin was an alloy of gold and silver and bore the symbol of the ruler. The metal token became a coin after being struck by hand on a hammer that bore an imprint. The blow imprinted the imprint on the face of the coin. Another inscription found on the anvil stamped the back of the coin. The transition to silver and gold coins accelerated the spread of the coin throughout the Greek world and from there to the rest of the ancient world. After Alexander’s conquests, thousands of local imperial mints were spread throughout the ancient world that minted gold, silver and bronze coins. Transition to use Economically, the coins were used as propaganda tools. New coins announced the change of emperors, victories in battles and were even used in the Jewish revolts as a declarative tool to declare independence.

Bibliography

Casey, J. and Reece, R. (eds.) 1989. Coins and the Archaeologist. London.

Howgego, C. J. 1995. Ancient History from Coins. London.

Kemmers, F. and Myrberg, N. 2011. Rethinking Numismatics. The Archeology of Coins. Archaeological Dialogues 18 (1): 87–108.

Mashorer, 10th year 1998 (1997). Treasury of Jewish Coins. Jerusalem.

An archaeological layer is a local archaeological unit that has a defined beginning and end and has cultural characteristics. In an archaeological site, a stratum is the entire set of remains that existed in the past in a certain period of time and originated in a structure, a settlement.

The Amarna Letters are among the most significant discoveries in the study of the archaeology of Israel and the ancient Near East. This collection consists of hundreds of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform script, primarily in the Akkadian language. The letters were found in Egypt at the site known as Tel el-Amarna, dating to the Late Bronze Age. This site is identified as the capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten (14th century BCE). The first letters were discovered in 1887 by local residents. Initially, they were sold to antiquities collectors and eventually made their way to museums worldwide. Additional letters have been unearthed through both looting and organized archaeological excavations.

A minority of the letters were sent by rulers of other kingdoms, such as the kings of Mitanni, Ugarit, and Babylon. These letters shed light on Egypt’s diplomatic relations and the connections between the great empires of that era. The Amarna Letters are particularly valuable for the study of Canaan during the Late Bronze Age, providing information on the political situation in the mid-14th century BCE.

Most of the letters were sent by local Canaanite rulers to various pharaohs. Among the cities mentioned are Hazor, Megiddo, Akko, Shechem, Gezer, Gath, Jerusalem, Gaza, Ashkelon, Lachish, and others. The recipients of the letters were various officials within the Egyptian Empire. The correspondence often followed a fixed format, wherein the subordinate rulers referred to themselves as ‘hazannu’ (city governor, a rank lower than ‘king’) and depicted themselves as bowing down seven times and seven times before the pharaoh they addressed.

The Apiru: Canaan’s Mysterious Raiders

Many of the letters describe the activities of a mysterious group referred to as the ‘Apiru’ (or Habiru) operating in the Canaanite region during the 14th century BCE. According to the letters, the Apiru’ attacked various Canaanite cities, such as Megiddo and Ta’anach, and robbed travelers. The repeated appeals from Canaanite governors to the pharaohs suggest that the pharaohs, particularly Akhenaten, often ignored these governors and did not assist them when they were attacked by the Apiru’. This neglect led some Canaanite city-states, like Shechem, to revolt against the Egyptians.

The letters reflect a period of decline in the Egyptian Empire, during which the northern provinces of the kingdom were neglected. This neglect necessitated numerous Egyptian military campaigns in subsequent generations to regain control over the region.

Scholars debate whether the Apiru can be identified with the Hebrews (Israelites). Most researchers believe the groups were not identical. The Apiru were undoubtedly a multi-ethnic group, whereas the Hebrews/Israelites represented a specific ethnic group. Additionally, the etymological connection between the names is unclear. Some scholars, however, suggest a possible link between the groups. This is partly due to a potential etymological connection and the fact that the Apiru operated in regions similar to those conquered by Israel during the period of conquest and settlement. Furthermore, two of the letters mention ‘men’ and ‘soldiers of Judah.’

Sources:

Y. Bin Nun, ‘Hebrews and the Land of the Hebrews’, Megadim 15 (1992), pp. 9-26.

Y. Elitzur, ‘Dating the Letters of the King of Jerusalem in the Amarna Archive and the Settlement in Bethlehem: An Appendix to the Paper Bethlehem in the Time of the Conquest of the Land and the Days of the Judges’, Hebron and Judah Studies 5 (2016), p. 39.

M. Jastrow, Jr., ‘“The Men of Judah” in the El-Amarna Tablets’, Journal of Biblical Literature 12 (1893), pp. 61-72.

W. L. Moran, The Amarna Letters, Baltimore and London 1992.

Na’aman N., ‘The Egyptian-Canaanite Correspondence’, in: R. Cohen and R. Westbrook (eds.), Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of Internation Relations, Baltimore and London 2000, pp. 125-138, 252-253.

The Byzantine period began in the 4th century AD and concluded in the 7th century AD. The transition from the Roman era to the Byzantine era is marked by two events. First, Emperor Constantine’s reign (306-337 AD), who embraced Christianity and established it as the official religion of the Roman Empire. Second, the division of the Roman Empire in 395 AD into the Western Empire and the Eastern Empire. The latter became known as the “Byzantine Empire.” The name “Byzantine” originates from the Greek city of “Byzantion.” Constantinople, the capital of the empire (named after Emperor Constantine), was built on Byzantion’s ruins. Lasting for approximately a millennium, the empire ruled over southern Europe, the Middle East, and Egypt. However, the Byzantine period in the Levant concluded with the Arab conquest of Jerusalem in 634 AD.

The Byzantine Empire aimed to oversee the holy sites mentioned in the Old and New Testaments. They suppressed dissent from Jewish and Samaritan communities. Christianity constituted the majority religion during this era, peaking at around 2.5 million adherents (compared to approximately 200 thousand Jews). Notably, churches and monasteries were constructed in significant locations such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Capernaum, and Mount Tabor. These attracted pilgrims from across the Christian world who sought to worship and honor the relics of saints. Moreover, Byzantine emperors undertook the renovation and expansion of the Temple Mount and erected the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This period was marked by political, religious, and cultural transformations, as well as conflicts, uprisings, and invasions. It witnessed the evolution of Christianity, literature, and theology alongside the emergence of various sects and religious doctrines.

Jews, Samaritans and Pagans

During the Byzantine period, the Jewish and Samaritan communities, once relatively autonomous and prosperous under Roman rule, faced oppression and decline. Byzantine emperors implemented laws restricting the rights and liberties of Jews and Samaritans. These included bans on holding public office, military service, land ownership, circumcision, holiday observance, and entry into Jerusalem. Despite several rebellions—such as those in 484 AD, 529 AD, and 614 AD—against Byzantine oppression, these communities were brutally suppressed by imperial forces. For instance, the Gallus Rebellion of 351 AD, an attempted Jewish uprising, resulted in the destruction of Beit Sha’arim and the imposition of a military regime in the region.

Meanwhile, archaeological excavations from the same period reveal religious diversity and syncretism. While Christianity predominated, the findings suggest a coexistence of various religious traditions, including Judaism, Samaritanism, and paganism. Synagogues dating to the Byzantine era, like those discovered in Beit Alfa and Capernaum, feature intricate mosaic floors adorned with biblical scenes and Jewish symbols. This era also witnessed a surge in the dissemination of Jewish mysticism and rabbinic literature, alongside the compilation of the Jerusalem Talmud and the Midrash of the Amoraim.

The Samaritan community, centred around Mount Gerizim, thrived throughout the Byzantine period. Excavations conducted in Samaritan synagogues and residences yield valuable insights into their religious practices and cultural identity. Additionally, archaeological findings suggest the persistence of pagan worship and rituals in rural areas, with temples dedicated to deities like Dionysus and Pan, indicating the coexistence of pre-Christian religious traditions alongside the spread of Christianity.

Archaeology, economy and trade

Numerous Byzantine archaeological sites dot the landscape of Israel, showcasing layers of Byzantine settlement, churches, and monasteries. Over the years, excavations have unveiled significant discoveries, including a massive wine factory in Yavne producing approximately 2 million liters annually. Churches abound in regions like the Negev, Judean lowlands, northern areas, and along the coastlines. These excavations have unearthed a diverse array of artifacts—pottery, coins, lamps, glassware, metals, and bones—illuminating the rich tapestry of daily life, trade, and economy during this era. Notable sites include Caesarea, Schytopolis (Beit Shean), and Sepphoris (Tzipori).

Throughout the Byzantine period, trade networks thrived and expanded across the Land of Israel. Excavations in port cities like Acre and Ashkelon have uncovered evidence of maritime trade routes linking the Mediterranean world, the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. Discoveries of typical pottery, glassware, and coins at these sites attest to the region’s integration into the broader economic sphere under Byzantine influence. Furthermore, agricultural prosperity flourished with innovations such as terraced agriculture and irrigation systems, fostering the development of urban hubs and rural settlements. Olive oil, wine, and grain production emerged as vital components of the region’s economy, supported by archaeological remnants and historical records.

External threats

Amidst the Byzantine period, the region confronted repeated threats and invasions from external adversaries, including the Sasanian Persians, Arab tribes, and Turks. In 614, the Persians successfully seized control of the region, resulting in the destruction of numerous churches and monasteries, the massacre of thousands of Christians, and the temporary reinstatement of Jewish governance in Jerusalem. Although the Byzantine Empire reclaimed the territory in 629 AD, its local dominion endured only for a brief period until the advent of Islam and the Arab conquest of the Land of Israel in 634 AD. (The Byzantine Empire persisted elsewhere until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD.)

In summary, the Byzantine era stands as one of the most pivotal and influential periods in the history of the Land of Israel. It witnessed profound religious and cultural shifts, leading to an unparalleled demographic zenith that remained unmatched until the establishment of the State of Israel. This period marks the transformation of the Levant into a revered holy land and the inception of Christian pilgrimage. Moreover, it holds significance for Judaism, notably with the activity of the Amorites. Historically, the conclusion of the Byzantine period signifies the transition from antiquity to the onset of the Middle Ages.

b'

The ‘Beka’ weight is a type of ancient weight used in the Land of Israel during the Iron Age (the 12th century BCE-586 BCE). The ‘Beka’ weight did not have a single unified standard denomination, likely because it represented half of the weight of the ‘Shekel’ weight, and there were a few types of ‘Shekel’ weights. Usually, the ‘Beka’ weighed between 5.66 and 6.65 grams. Prior to the Persian period (539-332 BCE) coins were not used as a method of payment, and so weights were used to measure the amount of silver (and occasionally also gold) used for payment.

‘Beka’ weights were first discovered when the American archaeologist Charles Torrey bought such a weight from an antiquities merchant in Jerusalem. Later, more such weights were discovered in archaeological excavations around the Land of Israel. An examination of the different weights confirmed that words of the verse in Exodus 38:26 which presents the ‘Beka’ as the name of the half-shekel weight given as a donation to the Tabernacle. However, some researchers believe that the ‘Beka’ represented only the holy half-shekel and not half of other types of Shekels (the ‘LMLK’ Shekel and the regular Shekel). Variations in the sizes of different Beka weights may be understood as erosion of the weights or a reflection of a rise of descent in the value of the holy Shekel.

Sources:

L. Di Signi, ‘Weights and Measurements in Antiquity and Their Modern Presentation’, Cathedra 112 (2004), pp. 137-150 [Hebrew]

R. Y. B. Scott, ‘Weights and Measures of the Bible’, The Biblical Archaeologist 22 (1959), pp. 21-40

E. Stern, ‘Measurements and Weights’, The Biblical Encyclopedia, IV, pp. 846-878 [Hebrew]

C. C. Torrey, ‘Semitic Epigraphical Notes’, JAOS 24 (1903), pp. 205-226

Biblical archeology is a field of archeology that deals with findings from the Biblical period in the Land of Israel and its surroundings, and tries to reconstruct the history of the people of Israel and the other peoples of the land based on these findings. Those involved in this field uncover the archaeological evidence and try to interpret what is written in the Bible in light and evaluate the degree of reliability of the biblical report.

c'

The Chalcolithic period (4,500-3,600 BC) is one of the most significant and mysterious periods of change in the history of humanity. In the southern Levant, it is characterized by new human behaviours indicating growing social complexity, yet it shows inconsistencies and a large variety of phenomena between different regions. Many different cultures have been defined, exhibiting different behaviours and different material cultures. This abundant variation has caused much disagreement among scholars, and both the period’s chronology and which culture belong to it are disputed.

The Chalcolithic period follows the Neolithic period without a break and is differentiated from it by the appearance of significant new developments and additions:

The forming of the “Mediterranean Agricultural Package” – the collection of plants and animals which will continue to form the dietary and economic basis in the area for the rest of history. It contains cereals, legumes, olives, vine, goats, sheep, cattle, and swine. Additional plants that have been domesticated in this period were figs, pomegranates, dates and more. One of the innovative and important dietary and economical additions of the period is agricultural secondary use: manufacturing of milk and its products, wool, oil and wine, and the use of animals for carrying loads.

The beginning of copper utilization – as well as other metals like gold and silver. This new craft demonstrates the development of complex metallurgical knowledge and suggests a shift to specialized craftsmanship, and from domestic to more industrial production.

Changes in settlements’ size and dispersion – while settlements’ size varies, large settlements reach an unprecedented magnitude, while new settlements appear in arid areas that were never inhabited before.

Changes in material culture – there is a surge in art production in this period, while new artistic styles develop. Similar motifs appear in different areas of the southern Levant and on artefacts of different mediums, though there is still regional variation. In addition, the use of rare materials originating from distant regions increases – like obsidian, turquoise, and precious metals as gold and silver. These indicate the development of complicated and wide-spreading trading networks. The appearance of these unique materials and arts raises disagreements among scholars regarding social structure in the period: some scholars contend these suggest the beginning of social inequality, while others point to other social behaviours, like settlement structure and burial customs, which do not indicate class differentiation.

Sources;

Rowan, Y.M. (2014). The Southern Levant (Cisjordan) during the Chalcolithic period. In A.E. Killebrew, & M.L. Steiner (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000-332 BCE (pp. 223–236). Oxford University Press.

A jug with a collared rim is a jug that is often found in archaeological sites of Israeli settlements from the Iron Age 1 between 1150 and 1000 BC, a period defined as the period of tribal settlement.

It is the field of academic study of the Bible: the Bible, the outer books and the New Testament. Unlike traditional biblical interpretation, biblical criticism ignores the religious status of the text, and seeks to investigate it with philological tools like any other ancient text. Therefore, the main questions that arise in this field are: when, where , why and under what circumstances was a certain text written, what influences contributed to its design and what are the sources from which it was derived, such as the hypothesis of the certificates and the theory of sources

Casemate Wall is a defensive system that surrounded mound cities in the Land of Israel from the Late Bronze Age and especially during the Iron Age. The sphincter wall consists of an outer wall and an inner wall. Partition walls were placed in the empty space between the walls, with the aim of creating rooms. The rooms had access from the city and other rooms in the wall. The inner rooms were sometimes used as storage or living rooms. In times of war they were sometimes filled with dirt and earth and thus provided the city with more protection than any solid wall. Many towers were often built between the wall, the width of which exceeded the width of the wall. In the Land of Israel, gates to the city called cell gates were sometimes incorporated into the wall, which were wider than the wall and had several rooms to the right and left of the gate.

d'

In biblical criticism, the deuteronomistic view is the view attributed to the set of beliefs and opinions that were influenced by the “deuteronomistic source” or Deuteronomy, also called “Mishna Torah”. The origin of the word is in the name of the Book of Deuteronomy in the Septuagint translation into Greek and Latin – the Vulgate

The Documentary hypothesis (also the source theory, or the Graff-Wellhausen hypothesis) is the hypothesis that the five Pentacles of the Torah were compiled by unifying a number of earlier documents that constitute independent, parallel and complete narratives of the same myths. It is usually accepted to define four certificates, but the exact number is not the heart of the hypothesis. Today the theory is less accepted in the research world

A dating method based on measuring the thickness of rings in tree trunks. Every year a ring is added to the tree, the thickness of which varies depending on precipitation and other conditions. Using tree trunks that have overlapping rings between them, it is also possible to date wooden finds discovered in excavations. Using this method it is possible to build a timeline that goes back thousands of years.

e'

“Egyptian Blue” is a synthetic inorganic pigment made up of crystals of calcium-copper tetrasilicate (CaCuSi4O10), and is among the first synthetic inorganic materials that humans ever began to produce. The chemical combination of the pigment has also been identified in nature, but it is very rare, and synthetically it is produced in a complex process that requires heating and cooling for hours in precise and narrow temperature ranges, and under specific conditions.

The pigment was first identified archaeologically in ancient Egypt starting from 2,500 BC, and throughout its existence it was produced in large quantities, and was used for frescoes, ceramic glazes, faience, and glass. Its production decreased around the 6th century AD, and its use stopped completely from the middle of the century 9 AD until the end of the 19th century, possibly due to the complexity of its production.

source and for further reading

Warner, T. E. (2011). Synthesis, properties, and mineralogy of important inorganic materials. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. (פרק 3: ע”מ 26-49)

The Early Bronze Age period is the period in which urban settlements first appear in the southern Levant, and it is therefore considered a very important and influential period in the history of the area. Many of the cities that developed in this period appear in the bible, like Jerusalem, Megiddo, Hazor, and more. This period in the southern Levant is parallel to the development of the great civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The period spreads over 1,300 years, between 3,700 and 2,400 BC. This long duration of time is divided into four main stages:

Early Bronze Age 1a (3,700-3,300 BC)

Early Bronze Age 1b (3,300-3,100 BC)

Early Bronze Age 2 (3,100-2,900 BC)

Early Bronze Age 3 (2,900-2,400 BC)

The beginning of the period (Early Bronze Age 1a-b) is characterized by simple, rural villages, scattered and distant from each other. The structures and tools found in them are very simple. The economy was based on “Mediterranean package” agriculture: cereals, vines, olives, sheep, and cattle. The early stages of the period are also characterized by the presence and cultural influence of the kingdom of Egypt in the southwestern part of the area.

During the period (Early Bronze Age 2) the area underwent majour changes. The Egyptian presence disappeared as the settlements grew and became denser. Regional trade systems began to be developed, for instance, with Egypt, as well as the construction of public and cult buildings. The period’s findings show the emergence of social classes. Later on, the settlements were fortified, and an urbanization process began.

Significant differences between social classes are evident at the height of the period (Early Bronze Age 3) and the urbanization process, together with the abandonment of rural settlements for the well-fortified cities. At that time, the regional trade decreased.

The Early Bronze Age period ended with the collapse of the urban system, as the cities were abandoned. It seems the area’s populations went back to rural and nomadic subsistence strategies, often far away from the areas of the Early Bronze Age settlements, and the intermediate Bronze Age begins.

Sources

Shai, I. (Accessed on 5 June 2023). The Bronze Age 3,700-1,150 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/the-bronze-age/?lang=en

Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). (2019). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 1). Lamda – The Open University.

A biblical kingdom in the past of the Jordan and the Negev, located south of Moab, southeast of the Kingdom of Judah, west and north of the Arabian desert. Most of its former territory is now divided between southern Israel and present-day Jordan. Edom appears in written sources relating to the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age.

The Edomites appear in several written sources, among others in the Bible, a list of the Egyptian pharaoh Seti I from 1215 BC as well as in the chronicle of the campaign of Ramses III (1186-1155 BC). Archaeological studies have shown that the nation flourished between the 13th century and the 19th century 8 BC and was destroyed after a period of decline in the 6th century BC by the Babylonians. After the fall of the kingdom of Edom, the Edomites were pushed west towards southern Judea by nomadic tribes that came from the east; among them were the Nabateans, who first appeared in the historical chronicles of the 8th century -4 BC and already established their own kingdom in what was Edom in the first half of the 2nd century BC.

Their relationship with the people of Israel was controversial. In the Bible, the Edomites are described as relatives of the Israelites (descendants of Esau, Jacob’s brother) but also as their bitter enemies, with whom there were many conflicts.

The ferrous copper industry in Pinan and Timana is attributed to the kingdom of Edom.

f'

Those who accept the historical chain of events described in the Bible as written and tongue-in-cheek and are willing to accept external evidence only if it does not contradict the biblical story

g'

The ‘Gerah’ weight is a type of ancient weight used in the Land of Israel during the Iron Age (the 12th century BCE-586 BCE). There is a disagreement among researchers whether the ‘Gerah’ constituted 1/20th of a ‘Shekel’ or 1/24th of a ‘Shekel’. Per the first view, the ‘Gera’ probably weighed on average about 0.569 grams. Per the second view, the ‘Gerah’ probably weighed on average about 0.47 grams.

‘Gerah’ weights were first discovered by Irish archaeologist Robert Macalister during his excavations at Tel Gezer. These miniscule weights were inscribed only with hieratic (one of the ancient Egyptian forms of writing) numerals. Later, many more such miniscule weights were discovered all over the Land of Israel, with different measurements and different hieratic numerals. It was hypothesized by some researchers that inscribing the name of the weight upon such a tiny object was a difficult task and would have also significantly eroded the weight, thus decreasing its value (unlike larger weights). It should be noted that a ‘1-gerah’ weight has yet to have been uncovered. So far, only weights representing multiple gerot (plural of gerah) have been found (such as 3 gerah, 5 gerah, etc).

The word ‘Gerah’ as the name of the miniscule weights within the ‘Shekel’ weight system was taken both from the Bible and from the similar weight system used in Babylon and Assyria, which included a weight called a ‘Giru’. In 2003 an ostracon from the Judah hill country was published. This ostracon described two monetary transactions and mentioned the Hebrew word ‘[G]RH’ ([Ge]rah) beside the icon the symbolizes the ‘Shekel’, which verified the ‘Gerah’ being part of the ‘Shekel’ system.

Sources:

G. Barkay, ‘Iron Age Gerah Weights (Pls. נה–נו)’, in: B. Mazar (ed.), Yohanan Aharoni Volume (Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies 15), pp. 288-296

E. Eshel, ‘A Late Iron Age Ostracon Featuring the Term לצדכן’, IEJ 53 (2003), pp. 151-163

R. Kletter, Economic Keystones: The Weight System of the Kingdom of Judah, Sheffield 1998

R. Kletter, ‘’Four hundred shekels of silver, what is that between you and me?’ (Genesis 23:15): Weights and Weighing in Eretz Israel in Antiquity’, in: O. Ramon et al (eds.), Measuring and Weighing in Ancient Times (Catalogue 17), Haifa 2001, pp. 1-7 [Hebrew]

R. A. S. Macalister, The Excavation of Gezer: 1902-1905 and 1907-1909 – Volume II, London 1912

h'

An approach led by, among others, Yosef Garfinkel and Saar and Ganor, regarding the existence of a kingdom in the days of King David and the existence of cities in Judea as early as the 10th century BC. Hence, it is impossible that the transition from a rural society of the Iron Age I to an urban society of the Iron Age II in Israel and Judah only occurred Around 900 BC, as the low chronology approach

The ancient Hebrew script, also known as the Daetz script, is a script of the Hebrew alphabet that was used among the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Judah and the Kingdom of Israel in the first half of the first millennium BC.

The House of the Four Spaces or the Israeli House is a type of building that was discovered at many excavation sites throughout the Land of Israel and abroad. It originated in the Late Bronze Age, after which it was adopted by the new settlers who began to inhabit the mountain area in the Land of Israel during the Iron Age, and who later became known in the ninth century BC as the “Kingdom of Judah” and the “Kingdom of Israel”. Because of this, it is a characteristic of an Israeli settlement point during the Iron Age (“the Israeli period”).

The Hellenistic period – 323 BC – 30 BC

In 333 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Syria and Israel after two hundred years of the Persian Empire. After his death in 323 BC, a political and military competition began between the generals in Alexander’s army (called “Diadochus”) for the inheritance of the empire he founded. The Land of Israel was one of the centers of the struggle between the House of Ptolemaic who lived in Egypt and the House of Seleucids who lived in Syria, in a series of battles called the Syrian Wars. Between 301 BC and 200 BC, the land of Israel was ruled by the Ptolemais, and between 200 BC and 103 BC, the Seleucids ruled.

In the Persian period, religious-ritual autonomy was introduced in the Jewish region. This practice also continued in the Hellenistic period, along with the spread of Greek-Hellenistic civilization which gradually merged with the cultures of the East, including in the Land of Israel.

The current leading approach in research holds that economic-commercial interests are at the foundation of the spread of Hellenistic culture, this contrasts with a previous research approach which believed that these were cultural motives. Many of the inhabitants of Judah adopted the Hellenistic culture and customs and were therefore called “Hellenistic”.

In 169 BC, Antiochus IV invaded Jerusalem, taking advantage of an intra-Jewish conflict. He looted the treasures of the Temple and passed decrees that harmed Jewish religious autonomy, such as a ban on circumcision, etc. These decrees were the motive for the outbreak of the Hasmonean Revolt, which took advantage of the weakness of the empire. Following these decrees, the Hasmonean rebellion broke out, establishing an independent Jewish regime in the Land of Israel for eighty years, from 140 BC until the takeover by the Roman Empire in 63 BC.

Archaeological evidence from the Hellenistic period in the Land of Israel indicates the integration of this culture into religious and cultural life. The Greek language, along with Hellenistic names and customs appear in the findings, mainly among the urban population such as in Jerusalem, Beit Shean and along the coast. The Hellenistic usually came from the upper class and the priesthood. One example is the high priest in Jerusalem in 175-172 BC who changed his name from Joshua to Jason after a Greek mythological hero.

An examination of the architectural findings shows that the Hellenistic citadels and places of worship continued local building traditions.

Professor Tcherikover writes that the term “polis” in the context of the Israeli land is not the establishment of a new Greek city, but rather the acceptance of the Greek constitution by an existing city, which took on a new Greek name and went through processes of social Hellenization. Prof. Oren Tal maintains that Hellenism in the Land of Israel was partially assimilated and manifested mainly in areas of administration such as: language, script, coins, establishment, officials and military aspects. Other architectural findings are mainly military such as citadels, forts and ramparts. In some of them, the use of an administrator is evident, and they may explain the relative absence of administrative public buildings from this period.

Evidence of the Hellenistic administration appears in the small find in several main sites that were excavated, including Tel Michal, Tel Anapah, Dor, Nablus, and Tel Kadesh. Coins, seals, stamps, scales, and other epigraphic findings were found at these sites. The numismatic finds are divided between autonomous urban minting approved by the ruler, and state coins. Another Hellenistic influence in the Israeli territory is evident in weapons, and in particular the presence of lead sling stones that sometimes bear inscriptions and iconography. Also, this period is characterized by many technological innovations, such as glass and ceramic production processes. Other significant changes are in the ranks of the manager and the fields of philosophy and sports.

Many researchers claim that Hellenism should not be seen as a culture that was imposed on the East, but rather, a period in which Eastern and Western cultures merged in religious-cultural-economic and technological aspects into a new cultural entity, which reached a more complete cohesion in the Roman period. According to this approach, the Hellenistic period in the Land of Israel must be seen as a period of direct continuation of traditions on the one hand, and on the other hand the beginning of cultural fusion and integration between East and West.

Bibliography

Tal, Oren. 2007. “The Land of Israel in the Hellenistic period – an archaeological aspect”. Antiquities: a journal for the antiquities of the Land of Israel and the lands of the Bible. Issue 13, pp. 2-14.

Tal, Oren. 2007. The Archeology of the Land of Israel in the Hellenistic Period: Between Tradition and Innovation. Bialik Institute, Jerusalem.

i'

The Iron Age I (1200—980 BC*), the first sub-period of the Iron Age in the southern Levant, began after the crises of the end of the Late Bronze Age period, and the political, economic, and cultural changes they caused: the period’s empires weakened or collapsed, and its characteristic international trade ceased. In the southern Levant cities were destroyed, international relations broke off, and a period of isolated regional and internal development commenced.

The Iron Age I is a transition period from the Canaanite political, ethnic, and cultural reality of the Bronze Age to a new reality consisting of a new political order, and new peoples and cultures. Therefore, the period is characterized by a new cultural diversity, as in some areas the Canaanite customs and material culture continued, and in others new ones appeared.

The period is divided into two parts:

The Iron Age Ia (1200—1135 BC) is also called “Late Bronze Age III” or “Transition Period Late Bronze-Iron”. During the period the sovereignty of the 20th Egyptian dynasty in the Levant continued, and so did the hegemony of the Canaanite culture, while at the same time the new cultures/ethnic groups which will continue to develop and define the Iron Age appeared, manifesting distinctive material culture: the Proto-Israelites, the Phoenicians, and the Philistines.

The Philistines are identified in the western Shephelah, especially in Ashkelon, Ekron, Tel-Ashdod and Gath. They are associated with the Sea Peoples and with a distinctive material culture which shows Aegean, Cypriot and southern Anatolian influences, and are understood as an immigrating culture.

In the central hill country of Israel, in the Jordan Valley and its eastern bank, and in the northern Negev many new rural settlements have been identified, and are understood by some scholars as the emergence of the Israelites. The origin of this population is disputed: some contend they originate in immigrants from the eastern bank of the Jordan River; in the coalescence of refugees from the Canaanite cities which were destroyed at the end of the Bronze Age; that they developed as a new social-political formation of the local population; or as a combination of all these social phenomena.

In the Iron Age Ib (1135—980 BC) the cultural changes that began in the Iron Age Ia took root: while Canaanite cities like Megiddo and Gezer continued to thrive, the new cultures blossomed beside them: in the southern coast of Israel the Philistines developed monumental building enterprises, and their material culture have been found at sites outside their initial region of emergence, which has been interpreted as evidence of growing trade; settlement expansion; or assimilation within local peoples.

In the central hill country, the eastern Gilead, and the upper Galilee hundreds of new rural settlements with simple and meagre material culture have been identified, and are understood as agricultural familial-tribal societies. It is thought that, with time, their unification formed the Kingdom of Israel, and so they are called the Proto-Israelites. Some scholars contend their social structure corresponds with the biblical descriptions of the tribes of Israel in the Judges and Samuel books.

At the end of the period, along the northern Israeli and Lebanon coasts, the urban culture of the Phoenicians renewed the maritime trade, and settlement amounts increased in the Negev and the eastern bank of the Jordan River – a phenomenon attributed to nomad tribal groups and associated with copper production from the mines of Wadi-Faynan and Timna, and its trade.

The period ended with the desertion of many settlements in the central hill country, and the destruction of many cities across the southern Levant, among them Shiloh, Megiddo, Tel-Masos, and Tel-Qasile, followed by changes in settlement structure and material culture, heralding the Iron Age II period.

*Dates are according to Amihai Mazar’s method, and are debated among scholars: see also high chronology, low chronology.

Sources

Mazar, A. (Accessed on 29 October 2023). The Iron Age 1150—586 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/the-iron-age/?lang=en

Mazar, A. (2019). The Iron Age I. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 109—196). Lamda – The Open University.

Faust, A. (2019). The Iron Age II. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 197—321). Lamda – The Open University.

The Intermediate Bronze Age (2500-2000 BC) is a fascinatingly mysterious period in the history and archaeology of the southern Levant: chronologically it is confined between the Early and Middle Bronze Ages and shows, on the one hand, persisting characteristics from the previous period (therefore it is sometimes called “Early Bronze Age IV”), and on the other hand, it shows new features which will continue and develop in the following period (therefore it is sometimes called “Middle Bronze Age I”). Nevertheless, there are significant differences between the period and the periods surrounding it, which portray the Intermediate Bronze Age as a period of momentous social crisis.

The period is characterized by an abrupt change from the urban lifestyle of the Early Bronze Age to agrarian and nomadic lifestyles. New, temporary, or meagre agrarian villages replaced the fortified, sizeable Early Bronze Age cities, especially in areas that were not inhabited before nor after the period, including in arid regions. In the Early Bronze Age cities that continued to be inhabited during the period, new, modest, and meagre agrarian constructions were built.

The pottery of the period is diverse and changes regionally, and it points both to technological and artistic developments and to the continuation of traditional methods. Some ceramic groups show foreign stylistic influences, among them some originating in the cultures of the northern Levant. Scholars interpret these to testify of the strengthening ties of the northern with the southern Levant during the period, and some suggest that at the period the southern Levant’s cultural and political affinity shifted northwards, contrary to the strong Egyptian affinity that prevailed in the prior period.

The increased use of metal was prominent during the period: many metal tools were found, especially in burial contexts, and with them, new and significant metallurgic technologies appeared: even though the prior period is called the “Early Bronze Age,” due to the use of bronze in Egypt and Mesopotamia, in the southern Levant, the deliberate use of bronze alloy begins only in the Intermediate Bronze age.

Another outstanding attribute of the period is the large number and the features of burials: many cemeteries were discovered in Israel, in some of them hundreds of graves, in the building of which great effort was often invested. Mostly, each grave contains one or a few bodies, and offerings. Yet inhumation types are varied, and sometimes one cemetery will contain graves of different kinds.

Different interpretations were offered for the abrupt changes that occurred in the southern Levant in the Intermediate Bronze Age compared to the preceding period: the arrival of immigrating populations to the region (apparently from the northern Levant); internal social calamity in the region’s cities that led to the disintegration of the urban social structure and the creation of a new tribal one; alternatively, some suggest the calamity was caused by external, environmental causes, such as climate change.

Source:

Shai, I. (Accessed on 25 August 2023). The Bronze Age 3,700-1,150 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/%d7%aa%d7%a7%d7%95%d7%a4%d7%aa-%d7%94%d7%91%d7%a8%d7%95%d7%a0%d7%96%d7%94/

Greenhut, Z. (2019). The Intermediate Bronze Age. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 1) (pp. 259-329). Lamda – The Open University.

The Iron Age II (980—530 BC*) in the southern Levant is characterized by major political changes: in its beginning new kingdoms emerged – the kingdoms of Israel, Judah, Ammon, Moab, Edom, and the Philistine and Phoenician cities. At its end, the region came under imperial occupation, which will continue until the Modern Era.

The period is the first in the region’s history for which abundant historical sources exist: the books of Samuel—Kings and some of the Prophets refer to the period, and were possibly written during it. Other historical sources, such as royal inscriptions and administrative documents, were found in the southern Levant, in Egypt, and in the Assyrian Kingdom.

The sub-division of the period and its dating are disagreed upon: the high chronology method begins the period at 1000 BC, while the low chronology at the last third of the 10th century. Yet it can be divided into 4 sub-periods:

The Iron Age IIa (980—830 BC) begins after the destruction of several cities in Canaan, among them Megiddo and Shiloh, and is characterised by material-cultural changes. The extensive rural settlement in the central hill country of the Iron Age I diminished, and cities, containing unique monumental architecture, like Mizpah and Samaria, emerged. Some inscriptions have been discovered, predominantly in the north of Israel, as well as stamp impressions in Jerusalem, and new settlements and forts in the Negev, which are associated with extensive activity in the wadi-Feynan mines.

While no historical sources have yet been associated with the period, the “United Monarchy” described in the biblical Samuel and Kings books is ascribed to it. The Monarchy’s existence is not explicit in the archaeological record and is disputed among scholars. The continuation of the biblical description of two kingdoms, Israel and Judah, is more evident in the archaeology, and corresponds to the described strength of the Kingdom of Israel, and its warring against the Kingdom of Aram, and royal and public monumental buildings have been discovered in its cities. Judah’s status at the time is disputed, as some scholars contend it became a significant kingdom only in the 9th century BC, and under Israel’s shadow. At the same time, the Phoenician kingdoms developed a flourishing trade network, extending over the Mediterranean Sea. Shishaq’s campaign, known from the Karnak Inscription and the Book of Kings is dated to the period, yet no archaeological evidence of it has been found, save a stele by Shishaq from Megiddo.

The Iron Age IIb (830—700 BC) began after the destruction of Gath, possibly by the kingdom of Aram, after which material-cultural changes are evident. It is considered a period of flourishing, especially in the kingdom of Israel, and is characterised by a significant increase in population and a renewal of the rural settlement. Significant social stratification, monumental building, international trade, use of writing, and administrative developments are evident in the Israelite Kingdom’s cities, which together with the historical sources tell of its becoming a significant regional power, competing with strong neighbouring kingdoms like Aram.

In the last third of the 8th century BC, the Assyrian empire gradually conquered the kingdom of Israel, killed and deported much of its population, and turned the region into Assyrian provinces. From this period until the end of the Iron Age the kingdom’s former regions became demographically and economically scant.

Meanwhile, the kingdoms of Tyre and Judah and the Philistine cities became Assyrian vassal states and continued to prosper: cities grew, monumental buildings were constructed, and new settlements and forts were established. From the end of the period, evidence has been found for the use of writing and administration. Trade developed, and the Phoenicians expanded their international connections.

Yet the kingdoms’ uprisings resulted in Assyrian campaigns to the region, inflicting heavy destruction. The last one, Sennacherib’s in 701 BC, brought the destruction of the Shephelah region’s cities, their transfer from the sovereignty of the kingdom of Judah to Ekron, demographic decrease, economic ruin, and the end of the period.

The Iron Age IIc (700—586 BC) represents the Assyrian empire’s sovereignty over the southern Levant, under which its northern parts remained negligible Assyrian provinces, while in its south the vassal kingdoms continued to blossom: in Judah, cities grew, monumental buildings were constructed, and the Shephelah region was partially rehabilitated. New settlements were established in new regions, among them agricultural settlements, and forts – in which evidence for the use of writing and administration, and military presence was discovered. Tel-Hadid became an Assyrian administrative centre, and increased settlement was identified around it, in which evidence for the settlement of exiles was found. The material culture indicates developed international trade, as the Phoenician kingdoms continued to expand their relations and established trade colonies on foreign shores. Cities, like Ashkelon and Ekron, grew and blossomed in Philistia as well, and in the latter a large olive oil industry was established. Some scholars contend that the writing of parts of the bible began during this period.

At the end of the period, the Assyrian empire weakened, and the Egyptian kingdom managed to conquer parts of the southern Levant. Yet shortly after, the Babylonian empire violently conquered the region, instating destruction, death, and deportation: in 604 BC it destroyed the Philistine cities, and in 586 Judah, and brought the end of the period.

The Iron Age IId (586—530 BC) represents the Babylonian empire’s rule of the region. Archaeological findings from the period are meagre, and their interpretation is disputed. Some scholars see the period as a time of economic and demographic decline and ruin resulting from the Babylonian occupation. Others contend the Babylonian destruction centred on the cities, and that only the social elite was exiled, and most of the population and the rural regions were less harmed and managed to recover.

Parts of the bible are attributed to this period. Its end and the end of the Iron Age came with the conquest of the region by the Persian empire, and the onset of the Persian Period.

*Dates are according to Amihai Mazar’s method.

Sources

Mazar, A. (Accessed on 29 October 2023). The Iron Age 1150—586 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/the-iron-age/?lang=en

Mazar, A. (2019). The Iron Age I. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 109—196). Lamda – The Open University.

Faust, A. (2019). The Iron Age II. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 197—321). Lamda – The Open University.

The Iron Age period in the southern Levant (1200—530 BC*) is considered the first period to have relatively numerous historical sources: it corresponds historically to the biblical Judges and Monarchy periods depicted in the bible books of Judges—Kings and in some of the Prophets’ books, which according to some scholars begun to be written at this period. There are also non-biblical historical sources about and from the period. Archaeological finds sometimes correspond with the biblical texts and the historical sources, and sometimes contradict them completely, and these disparities have been discussed extensively in archaeological, historical, and biblical research ever since they began 150 years ago.

The period is characterised by significant cultural and political developments that changed the southern Levant completely. While during the prior period (the Late Bronze Age) it was governed by the Egyptian empire, and the Canaanite was the hegemonic culture, in the Iron Age the Egyptians left, and new cultural-ethnic entities developed and settled in the region, some of them originating in the area, and some of them alien: the Sea Peoples (predominantly the Philistines) the Israelites, and the Phoenicians. During the period they developed new political institutions: the Kingdoms of Israel, Judah, the Philistine city-states, and Phoenician Tyre, which established between themselves and with the other kingdoms and empires around them complex political relations. In the latter part of the period, they were conquered by new empires: the Neo-Assyrian and the Neo-Babylonian, and the southern levant became a part of a new, vast, and complicated political order. These occupations began a long period of imperial control in the region which will last until modern times.

There is disagreement among scholars regarding the sub-division and the dating of the period (see high chronology, low chronology). Yet it is agreed to separate it into two parts: the Iron Age I (approximately 1200—980 BC) – during which the cultural, ethnic, and political changes began, and the Iron Age II (approximately 980—530 BC) – during which the new regional kingdoms were established, and later on conquered and the area came under imperial-Mesopotamian governance. While the sub-division of these periods is not agreed upon, they can be parted in the following way:

Iron Age Ia – 1200—1135 BC.

Irong Age Ib – 1135—980 BC.

Iron Age IIa – 980—830 BC.

Iron Age IIb – 830—700 BC.

Iron Age IIc – 700—586 BC.

Iron Age IId – 586—530 BC.

*The dating is according to Amihai Mazar’s method.

Sources

Mazar, A. (Accessed on 29 October 2023). The Iron Age 1150—586 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/the-iron-age/?lang=en

Mazar, A. (2019). The Iron Age I. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 109—196). Lamda – The Open University.

Faust, A. (2019). The Iron Age II. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 197—321). Lamda – The Open University.

j'

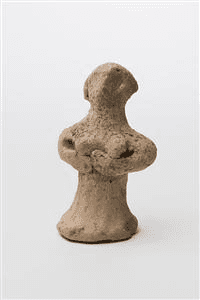

Judaic pillar figurines are a cultural find unique to the Kingdom of Judah, which began to appear in the area of the Kingdom of Judah in general, and Jerusalem in particular, at the end of the 8th century BC, and during the 7th century BC. During this period Judah was under the hegemony of the Assyrian Empire, followed by the Babylonian Empire. They disappeared with the destruction of Judah by the Babylonians at the beginning of the 6th century BC. Over a thousand figurines of this type, or their fragments, were discovered within the territory of the Kingdom of Judah. About 50% of the figurines were found in Jerusalem. Parallel to these figurines, figurines in the form of animals and riders were also common. horses

The figurines were usually made by hand from clay and shaped like a female body. They are about 15 cm tall and the upper part was designed in the image of a female body (naked or not – a matter of dispute), with the figure’s hands usually placed under the chest). The chest area was sometimes emphasized. On the other hand, reproductive areas were not shown in the female figurine. The lower part of The figurine was often tube-like and without legs, with a sunken base, sometimes hollow, for the purpose of standing.

The figurines are divided into two types according to the shape of the head. One, usually designed in a pattern that created facial features and even hair. The hair design was similar in outline to the Egyptian wig, which probably indicates a cultural influence. This part is connected to the rest of the piece with a lug/peg that is connected to the socket in the shoulder area of the figurine. The neck area was designed in an “unnatural” way, rough, accentuated or too long to cover the lug used to fix the head to the rest of the figurine. In the other type, as a “less complex” style, the head of the figurine was prepared manually by pinching and a simpler design. The pillar figurines were usually plastered with white, which was painted after conversion. Remains of black, yellow and red remained on the discovered items, in an attempt to emphasize the characteristics of the eyes, hair and jewelry.

Regarding the ritual interpretation of the figurines, different schools of thought hold that the figurines are a representation of various female deities (Ashrah, Ashtoreth or Anat). Other schools of thought believe that the figurines are a counter-reaction to the influence of the empires as an attempt to create a unique identity for the Jewish area.

l'

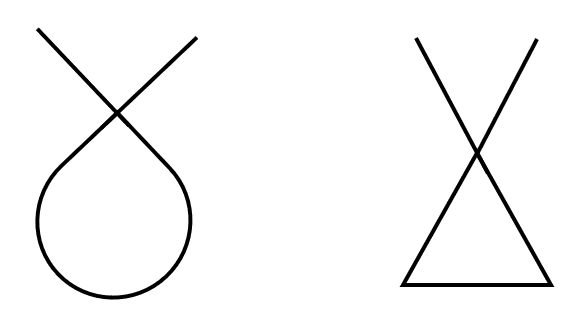

The ‘LMLK’ jar (Hebrew for ‘to the king’) is a type of jar that appeared near the end of the 8th century BCE in the Kingdom of Judah and disappeared around the mid-7th century BCE. The name of the jar comes from the type of stamp that decorated these jars’ handles: One of two winged symbols (a scarab/a circle) and around it the word ‘LMLK’ (‘to the king’). Often the name of one of four cities in the Kingdom of Judah was included in the stamp: Hebron, Zif, Socoh or MMST (which hasn’t been identified yet). The purpose of the jars was carrying liquids, likely wine and oil. The jars could hold between 39.75 liters to 51.80 liters.

‘LMLK’ jar handles were first discovered by British archaeologist Charles Warren in 1867 while holding excavations in Jerusalem. Since then hundreds of such handles have been found in sites such as Lachish, Ramat Rachel, Beit Shemesh, Timnath and more. There are two main theories surrounding the purpose of these jars: Wine and oil jars intended as tax payment to the Assyrian Empire or wine and oil jars stockpiled by King Hezekiah in preparation for his rebellion against the Assyrians. It is not known why there was a need for special stamps, given that other kingdoms in the area paid taxes to the Assyrians through wine and oil, but did not stamp their jars in a special way. Some have suggested that the stamps were intended to emphasize the rise of a new king – Hezekiah – and the changing of the face of the kingdom. Indeed, a similar winged symbol was found on a bulla carrying the signature of Hezekiah.

By Funhistory at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Premeditated Chaos using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18377205

By Funhistory at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Basilicofresco., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4852773

Sources:

Anonymous, ‘Phœnician Inscription on Jar Handles’ PEQFS 2 (1870), p. 372

A. Mazar, ‘Jar Stamps from Judah’, Qadmoniyot 54 (2021), pp. 56-58

N. Na’aman, ‘The lmlk Seal Impressions Reconsidered’, TA 43 (2016), pp. 111-125

D. Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973-1994) – Volume IV: The Iron Age and Post-Iron Age Pottery and Artefacts, Tel Aviv 2004

The Late Bronze Age (1550-1185 BC) follows the Middle Bronze Age and precedes the Iron Age I. During this period, the southern Levant came under imperial subjugation for the first time in history, as it was taken over and ruled by the New Kingdom of Egypt. This development was part of wider political processes happening in the era, pivotal for human history: empires, such as Hatti, Mitanni, Egypt and Asur began to emerge across the Ancient Near East, taking over large territories and populations, combating each other over them, and developing a complex diplomatic and commercial network. Between the emperors and empresses, and between them and the governors of the cities under their rule a correspondence system developed, remnants of which survived in royal archives found in archaeological excavations. Many of the letters refer to cities in the southern Levant, and this period saw the beginning of the use of writing in that region.

Nevertheless, archaeological research indicates that in Canaan during the period, the size of the cities, the rural area they controlled, and the sedentary population significantly diminished. Egyptian written sources tell of nomad populations living in the area and destabilising the regional urban system. Even though, an increase in material affluence and variety is evident in the material culture of the era: there was increased commerce in merchandise, raw materials, and luxury goods across the Ancient Near East, and in Canaan, the period is characterized by ostentatiousness.

The period is divided into sub-intervals:

The Late Bronze Age Ia (1550-1450 BC) – begins with the defeat of the Hyksos Dynasty in Egypt by the 18th dynasty. As part of it, the 18th Dynasty entered Canaan and conquered the city of Sharuhen (presumably Tell el-Ajjul). Destruction layers have been identified in many cities in the southern Levant of the era, dated across several dozens of years, and some scholars attribute them to the Egyptian conquest of the region (while others attribute them to internal or external crises). The period is characterized by a decrease in the number of settlements in Canaan.

In the Late Bronze Age Ib (1450-1400 BC) – Egypt began to establish its sovereignty over the Levant in a series of war campaigns, and the founding of imperial centres in Canaan, such as Gaza, Jaffa and Beit-Shean. Its dominion over the region was based on treaties with its cities’ governors.

The Late Bronze Age IIa (1400-1300 BC) – is dated to the same period as the Amarna archives in Egypt, which contain many correspondences between the Egyptian Pharaohs and the governors of the Canaanite cities under their rule (such as Megiddo, Lachish, and Jerusalem). These paint the disquieted political situation in Canaan during the period, which entailed territorial disputes between cities, conflicts with nomadic populations, and the Pharaoh’s commands and demands from the cities.

In the Late Bronze Age IIb (1300-1185 BC) – the 19th Dynasty which came to power in Egypt, intensified the Egyptian hold in Canaan: new imperial centres were built, like Tell el-Hesi, Gezer and Tel Afek, royal epigraph-bearing structures were erected, and the material culture hints of larger numbers of Egyptians in the region. Some scholars connect to this the rising numbers of settlements in the area during this period.

In the second half of the 13th and the 12th centuries BC undetermined processes brought the disintegration of the imperial structure of the Ancient Near East: empires dissolved and with them the international diplomatic and commercial networks. The region suffered from crises, hunger, and population movement. In Canaan many cities were destroyed, some recovered, and some were abandoned.

Late Bronze Age III (1185-1140) – the first half of the 12th century BC is named both Late Bronze III – due to the urban formation and the Egyptian presence in Canaan, and Iron Age Ia – due to the identification of new material culture characteristics suggesting the appearance of new populations/cultures in the area: the “Sea Peoples”, and the “Proto-Israelites”. Therefore, some call this period “Late Bronze-Iron I overlap”. From the second half of the 12th century BC the amount of Egyptian material culture in Canaan diminished, the Egyptian rule ended, and with it the Bronze Age in the southern Levant.

Sources

Shai, I. (Accessed on 23 September 2023). The Bronze Age 3,700-1,150 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/%d7%aa%d7%a7%d7%95%d7%a4%d7%aa-%d7%94%d7%91%d7%a8%d7%95%d7%a0%d7%96%d7%94/

Bunimovitz, S. (2019). The Late Bronze Age. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 12-107). Lamda – The Open University.

It was first proposed by Israel Finkelstein in 1996. According to this approach, the transition from Iron Age I (rural society in Israel and Judea) to Iron Age II (urban society in Israel and Judea) did not occur around 1000 BC, but only around 900 BC.

Hence, during the time of David and Solomon there was still a tribal social organization, living in villages, without formal cities and without centralized government. The paucity of findings from the excavations of Jerusalem, which is supposed to be the capital of the United Kingdom, allows such claims to be made.

m'

A school of biblical studies that sees the Bible only as a mythological narrative, without any historical basis.

The term is actually a derogatory term given by the opponents of the school

The first of the two central claims of the minimalists, is based on the premise that writing history is never objective, but includes the selection of data and the construction of a narrative using preconceived ideas about the meaning of the past. That history is never neutral or objective always raises questions about the accuracy of any historical account. The minimalists argue that the literary structure of the biblical history books is so obvious, and that the intentions of the authors are so clear, that scholars must be extremely careful in interpreting them properly. Even if the Bible does preserve accurate information, scholars do not have the means to sift through the information. This is one of the inventions with which he was mixed

The Middle Bronze Age is the 500-year-long archaeological period between 1950-1470 BC during which an abrupt change from a rural and nomadic lifestyle to an urban lifestyle occurred in the southern Levant. The urban and civic structure that developed in this period will continue in the southern Levant for the next 1000 years, through the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. It is one of the most populated periods in the history of the region and is characterized by the massive fortifications built in many of its cities, usually comprised of gigantic batteries that shaped most of the tels of Israel. In addition, the Proto-Canaanite alphabet was invented during this period, and for the first time in history, Canaan and its cities are mentioned in written sources: The Egyptian Execration texts mention the names of cities and kings from the region, like Ashkelon, Jerusalem, Hazor, etc.

Major economic and commercial developments occurred during the period, as complex, unprecedentedly wide-reaching terrestrial and maritime trade connections were established, spreading from Mesopotamia to Anatolia, Egypt, and the Aegean Sea. Accordingly, cultural influences became more prominent during the period, appearing in the fortified cities established along the Canaanite coast, like Ashkelon, Jaffa, and Acre. The urban civic structure began to develop around palaces which were the centre of financial and religious power, and across Syria and Mesopotamia, the Amorites gained control.

The period is divided into three sub-periods, the distinction between them based on gradual changes in pottery style:

During the Middle Bronze Age I (1950-1710 BC) settlements in the southern Levant were gradually fortified, monumental construction began, and an urban order comprised of cities, rural settlements and agricultural hinterland was established.

During the Middle Bronze Age II (1710-1590 BC) several cities in the southern Levant as Hazor and Ashkelon gained political power and grew into little city-states governing the settlements around them. Additionally, pottery from the period found in sites in Egypt allows its dating according to Egyptian written sources, as well as points to the development of the trade connections of the southern Levant, testified as well by Canaanite material culture discovered in Cyprus.

In the Middle Bronze Age III (1590-1470 BC) the urbanization process in Cannan peaked. The material culture in certain areas indicate strengthening ties with and/or influences from Egypt, together with an intensification of Canaanite participation in the maritime trade network, especially with Cyprus and the Aegean region. This period saw political changes in Egypt: its unification after the Hyksos dynasty’s defeat, which influenced southern Cannan: Tell el-Ajjul or Tell el-Far’ah (South) were subdued, and some contend the entire region came under Egyptian hegemony.

The end of the period and the beginning of the Late Bronze Age period is based on this historical event, which is known from Egyptian sources. No major change in the material culture is noted between the periods. Nevertheless, several Canaanite cities were destroyed at the end of the period over a timespan of dozens of years, and some connect these destructions with Egyptian attacks, inner political conflicts, or environmental factors.

Sources

Yasur-Landau, A. (2019). The Middle Bronze Age. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 1) (pp. 331-436). Lamda – The Open University.

n'

The Neolithic period (9,500-6,000 BC) was a significant stage in the development of human history, situated between the prehistoric eras, during which a hunter-gatherer lifestyle prevailed, and the urban periods, whose lifestyle we still follow today. During the Neolithic period, humanity experienced three majour changes:

First, for the first time in human history, people began to live in one place all year round, which initiated the construction of permanent buildings and property accumulation.

Secondly, during the period began the “Agricultural Revolution” – the domestication of plants and animals, and the 6,000-year-long transition from hunting and gathering to food production.

Thirdly, in the latter part of the period, humans began to produce pottery for the first time – a technology that will accompany humanity until today. Pottery survives well archaeologically and is found in sites from all time periods from this stage onwards, inferring much information on human cultures through history.

The Neolithic period is divided into two sub-periods:

The Pre-pottery Neolithic (9,500-6,400 BC), itself divided into three stages:

Pre-pottery Neolithic 1 (9,500-8,800 BC)

Pre-pottery Neolithic 2 (8,800-7,000 BC)

Pre-pottery Neolithic 3 (7,000-6,400 BC)

The second sub-period is the Ceramic Neolithic (6,400-6,000 BC).

The beginning of the Neolithic period (Pre-pottery Neolithic 1) is characterized by the first appearance in the history of humanity of permanent domestic buildings. The process of plant domestication began at this time with the intentional cultivation of wild plants, but human nutrition was mixed, also based on hunting and gathering. Later in the period (Pre-pottery Neolithic 2) the density of the settlements in the Southern Levant increased, their sizes were diverse, and signs of social inequality begin to show. At this stage, the economy was based mainly on domesticated leguminous plants and cereals, with the onset of goat domestication and continued meet acquisition through hunting. Some sites from the period show increased reliance on agriculture, while in others continued reliance on hunting. Additionally, new technologies appear, like plaster production. In the Pre-pottery Neolithic 3, goat and sheep domestication was completed, and evidence of regional trade appears.

In the Ceramic Neolithic period, the pottery industry appeared. Pottery is made differently in different cultures, along with other changing material culture characteristics, like settlement arrangement, building practices, and more. Three distinct cultures are recognized in the Southern Levant during this period: the Yarmukian culture in the north and centre parts, the Nitzanim culture in the southern coastal plain, and the Yericho IX culture between them: south of the first and north of the second.

Sources:

Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). (2019). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 1). Lamda – The Open University.

The ‘Netzef’ weight is a a type of ancient weight used in the Land of Israel during the Iron Age (the 12th century BCE-586 BCE). The ‘Netzef’ weight did not have a single unified standard denomination, likely because it represented 5/6 of the weight of the ‘Shekel’ weight, and there were a few types of ‘Shekel’ weights. Usually, the ‘Netzef’ weighed between 9.28 and 10.51 grams. Prior to the Persian period (539-332 BCE) coins were not used as a method of payment, and so weights were used to measure the amount of silver (and occasionally also gold) used for payment.

The ’Netzef’ weight was first discovered by the American archaeologist Frederick Jones Bliss during his excavations at Azekah (Tel Zakariya) in 1898. He had difficulty reading the letters upon the weights and suggested reading ‘NZP’. Other researchers suggested ‘NTzG’, ‘KSP’ and ‘NTzP’. A few months later two other such weights were found, and this time Bliss managed to read ‘NTzP’ (Netzef).

The word ‘Netzef’ doesn’t appear in the Bible. Some researchers have suggested interpreting the word in light of the Arabic word ‘Nitzaf’, which means ‘half’. Since the word is missing from the Bible, some have suggested that this weight was originally a foreign one which later found its way into the Israelite/Judahite weight system.

Sources:

G. A. Barton, ‘Two New Hebrew Weights’, JAOS 24 (1903), pp. 384-387

F. J. Bliss, ‘Second Report on the Excavations at Tell Zakariya’, PEFQS 31 (1899), pp. 89-111

D. Diringer, ‘The Early Hebrew Weights Found at Lachish’, PEQ 74, pp. 82-103

L. Di Signi, ‘Weights and Measurements in Antiquity and Their Modern Presentation’, Cathedra 112 (2004), pp. 137-150 [Hebrew]

R. Y. B. Scott, ‘Weights and Measures of the Bible’, The Biblical Archaeologist 22 (1959), pp. 21-40

p'

During the Persian period (539—332 BC) the southern Levant came under the occupation of the Persian empire (known also as the Achaemenid empire). The period holds considerable historical significance, as along its duration the southern Levant became a meeting ground between the cultures of the near-east and the Mediterranean cultures. The Western influence over the region intensified, and a process of cultural change commenced which would define the next 1000 years of Antiquity in the area, until the Middle Ages and the Islamic occupation of the region.

As the Second Temple period, during which the “Return to Zion” occurred, the period constitutes an essential episode in Jewish history: the Persian empire allowed the Jews exiled by the Babylonians to return to their land, rebuild their temple and cultivate their religion. During this period, the Pentateuch was set, and the Jewish religion as it is understood today was developed.

The period is considered a biblical period: some biblical books, like Isaiah, Ezra, and Chronicles, and other Apocryphal books like Judith, allude to the period, and some believe they were written during it. Additional sources about the period exist in Greek historiographies, such as the writings of Herodotus, as well as in contemporary documents which were found in the empire’s regions, like inscriptions, ostraca, papyri, and inscribed stamps.

The period began with the defeat of Babylon and the taking of its lands by the Persian empire in 539 BC. The new governors’ policies, which allowed the return of the Jews from Babylon, the spread of the Phoenician culture, and the establishment of the Edomites, created significant demographic and political changes in the southern Levant. Under their patronage, new political entities were established in the land of Israel: the Jewish state of Judah and the Samaritan state of Samaria in the inner hill country, the kingdom of Edom in the south of the country, and Phoenician hegemony in its coast and northern parts.

After the sparseness of the previous period, the Persian period was characterised by prosperity: the southern Levant’s settlements, including large cities from the Iron Age period, such as Samaria, Jerusalem, and Hazor, as well as villages, forts, and farmsteads, were restored and expanded. Fortifications and buildings were reconstructed, and administrative buildings and forts were built. The international trade led by the Phoenicians and the Greeks thrived, and large amounts of material culture imported from Egypt, Greece, and Cyprus, were found all over the region. In addition, glass and metal objects that were found testify to their increased use at that period (alternatively, increased preservation), and of technological developments in their production.

One of the most important developments of the period was the “Monetary Revolution” – the beginning of the production and use of coins in the southern Levant, and its change into a monetary economy. The first coins arrived from the Greek poleis at the end of the 6th century BC. In the second half of the 5th century BC, they were mostly Athenian, while at the same time, minting began in the Phoenician cities, like Tyre and Sidon, and in the Philistine cities, like Ashkelon and Gaza. In Samaria, Judah, and Edom, local minting began in the 4th century BC.

The coastal plain of Israel controlled by the Phoenicians was an important region during the period as it connected the East and the West, the Persian empire and the cultures of the Mediterranean. Many thriving cities were established along it during the period, including Acre, Dor, Jaffa, and Ashdod. The area served the Persian empire’s army in its war against the Greek poleis headed by Athens, in its occupation of Egypt, and in the handling of the latter’s revolts, which involved the temporary conquering of cities like Acre and Kabri, and the destruction of cities like Tel Abu Hawam and Tel Megadim.

The period ended with the conquering of the southern Levant by the Greco-Macedonian army of Alexander the Great in 332 BC, and the onset of the Hellenistic period.

Sources

Edrey, M. (Accessed on 8 November 2023). The Persian Period 586-333 BCE. Israeli Institute of Archaeology. https://www.israeliarchaeology.org/%D7%AA%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%AA/the-persian-period/?lang=en

Tal, O. (2019). The Persian Period. In Faust, A., & Katz H. (Eds.). Archaeology of the land of Israel: From the Neolithic to Alexander the Great (vol. 2) (pp. 323—411). Lamda – The Open University.

The ‘Pim’ weight is a type of ancient weight used in the Land of Israel during the Iron Age (12th Century BCE-586 BCE). The ‘Pim’ weight did not have a single, unified denomination, perhaps because it represented 2/3 of the weight of the ‘Shekel’ weight, and there were a few types of ‘Shekel’ weights. Typically the ‘Pim’ weight was somewhere between 7.18 grams and 8.13 grams. Before the Persian period (539-332 BCE) coins were not used as a form of payment, and so weights were used to measure the amount of silver (and occasionally also gold) needed for payment.

By User:Funhistory – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24528458