Samaria (Shomron in Hebrew), the capital of the Kingdom of Israel, is situated on an elevated hill called “Mount Shomron.” Surrounded on three sides by fertile valleys with tributaries of the Shechem stream, the city played a crucial role in Israel’s history. An ancient route passed near the site, connecting the Samarian highlands from north to south. Excavations at Samaria have illuminated its rich history as a large and powerful royal city, the seat of 14 Israelite kings. Omri and his successors, especially his son Ahab, established Samaria as an international and opulent city with a palace, public structures, warehouses, and expansive courtyards with pools.

Ezekiel later referred to Samaria as Jerusalem’s “older sister,” emphasizing its significance. The inhabitants around it, known as the Samaritans, were named after the city. Samaria was involved in Mediterranean trade, fostering relations with foreign cultures. Ahab’s political alliance with Sidon through marriage to Princess Jezebel drew criticism from the prophets. After its conquest by the Assyrians, Samaria experienced influence from various ruling powers, including the Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Hasmoneans, and Romans. Herod changed its name to “Sebastia,” a name still preserved in a nearby Palestinian village.

Mount Shomron, looking southwest. The Upper and Lower cities can be seen.

Research history

Two main expeditions have excavated Samaria. Harvard University conducted the first expedition between 1908-1910, exposing the palace of Israelite kings and revealing Hellenistic and Roman city remains. It was headed by Gottlieb Schumacher and George Andrew Reisner The second expedition, the “Joint Expedition” from 1931-1935, involved five institutions and revealed Samaria Ivories, Israelite burials, and more from the Roman city. The institutions involved were Harvard University, Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), British Academy, British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. It was headed by John Winter Crowfoot and among its participants are Kathleen Kanyon, as well as Eliezer Sukeinik and Nachman Avigad

Excavating the site has been challenging due to past construction works, causing distortions in the stratigraphic sequence. Archaeologists, including Lary Stager, Ron E. Tappy, and Norma Franklin, have worked since the 1990s to reevaluate the excavation results.

Mount Shomron before Shomron: “Shemer’s estate”

Samaria is unique among Israelite and Judahite sites. While most cities were built on the ruins of earlier ones, Samaria was established directly on bedrock. The Bible recounts how Omri purchased the hill from a man named “Shemer” with a substantial amount of silver and named it “Shomron” in his honor (1 Kings 16). The remains of an agricultural estate dating to the Iron Age I period (11th-10th centuries BCE) were discovered under the foundations of the Israelite palace. It contained over a hundred installations for wine and olive oil production. The westward shift of the capital from Shechem and Tirzah highlights Omri’s territorial ambitions, particularly toward the Mediterranean coastal plain. Some suggest Omri, took the crown by force, aimed to utilize the estate for economic power. Others suggest he was possibly influenced by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II who also left the capital in Ashur and established a new capital in Nimrud.

Samaria under the Omride Dynasty (882-841 BCE)

The Israelite royal palace, the largest in the southern Levant during the Iron Age, and among the most lavish in the Near East, was a key feature during the Omride Dynasty. Two hewn caves within the palace were suggested by Norma Franklin as burial sites for the Omride Dynasty, following a Mesopotamian tradition of burying members of the royal family within the royal palace.

The palace, situated on a manmade rock scarp of 30 dunams, featured well-dressed ashlar walls in the “headers and stretchers” method. Surrounding structures in the “upper city” or “acropolis” included a gate with proto-Aeonic capitals which was suggested as the location of a marketplace mentioned in 2 Kings 7. The “lower city” was also formed by altering the bedrock, surrounded by an impressive casemate wall. This building style is known as “Omride Architecture.”

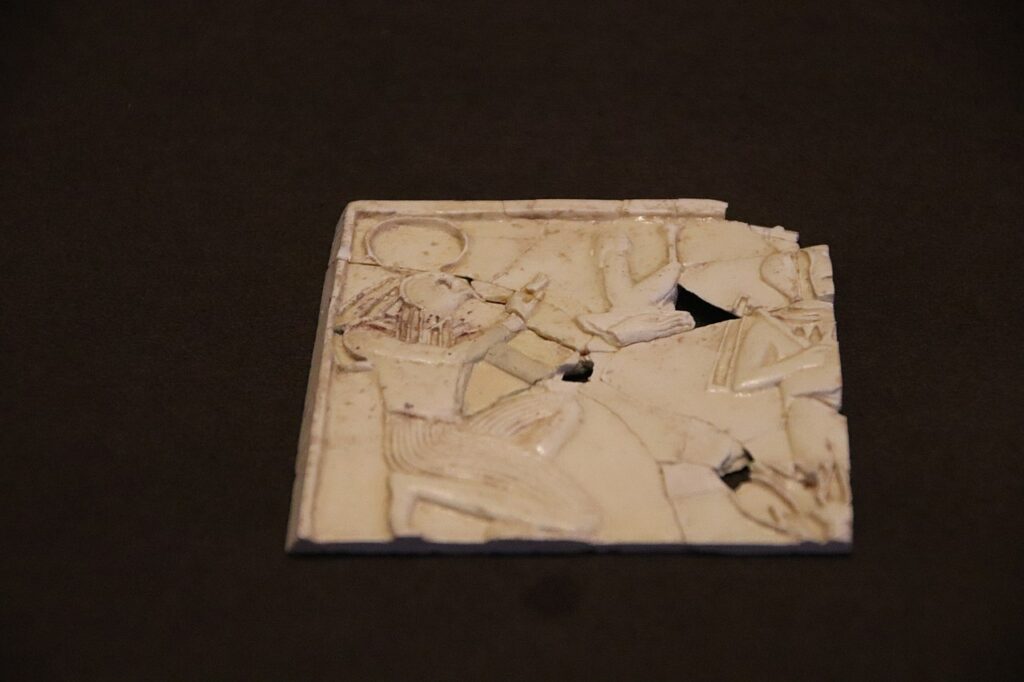

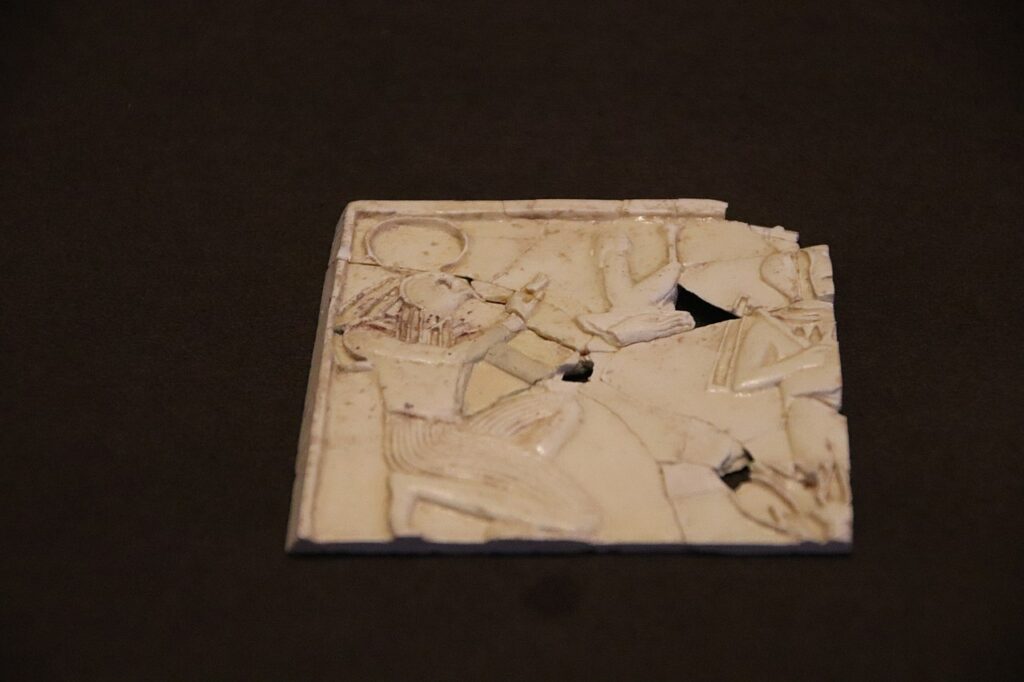

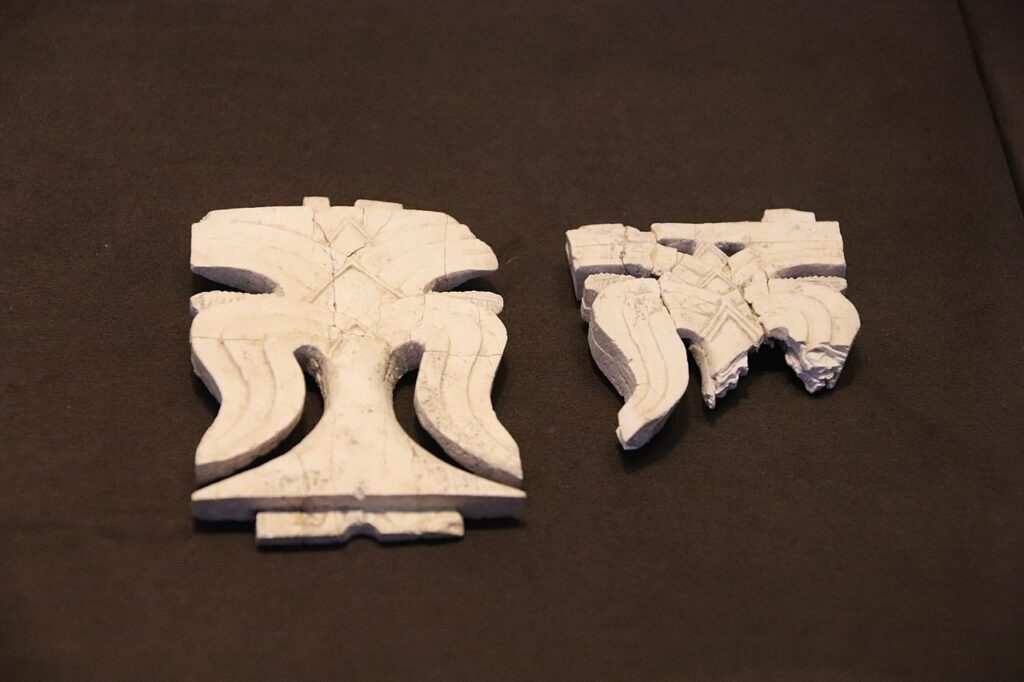

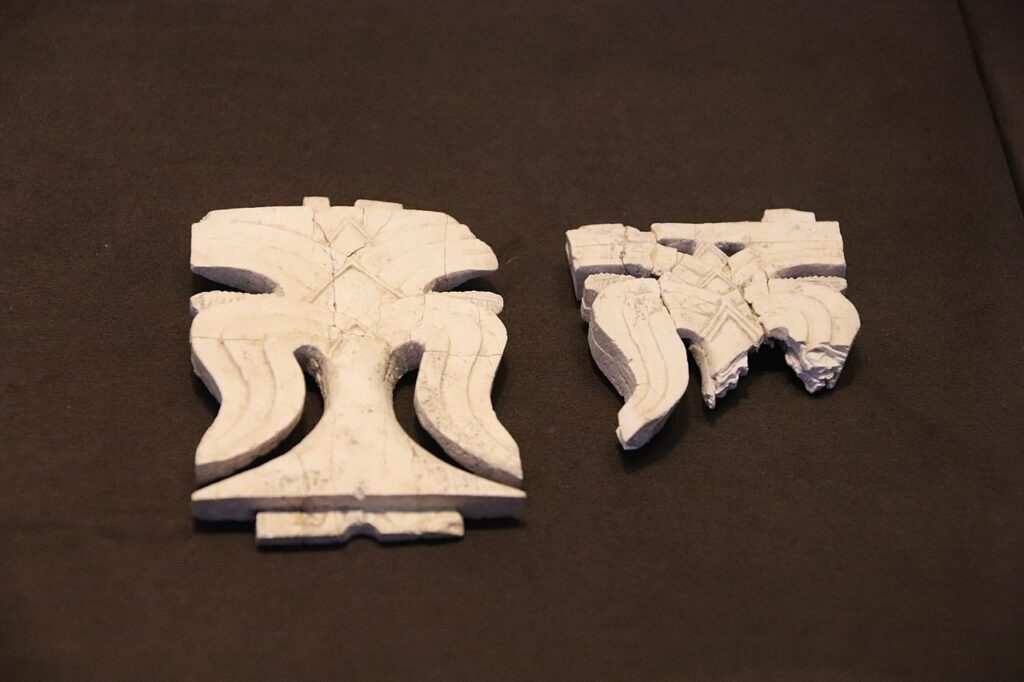

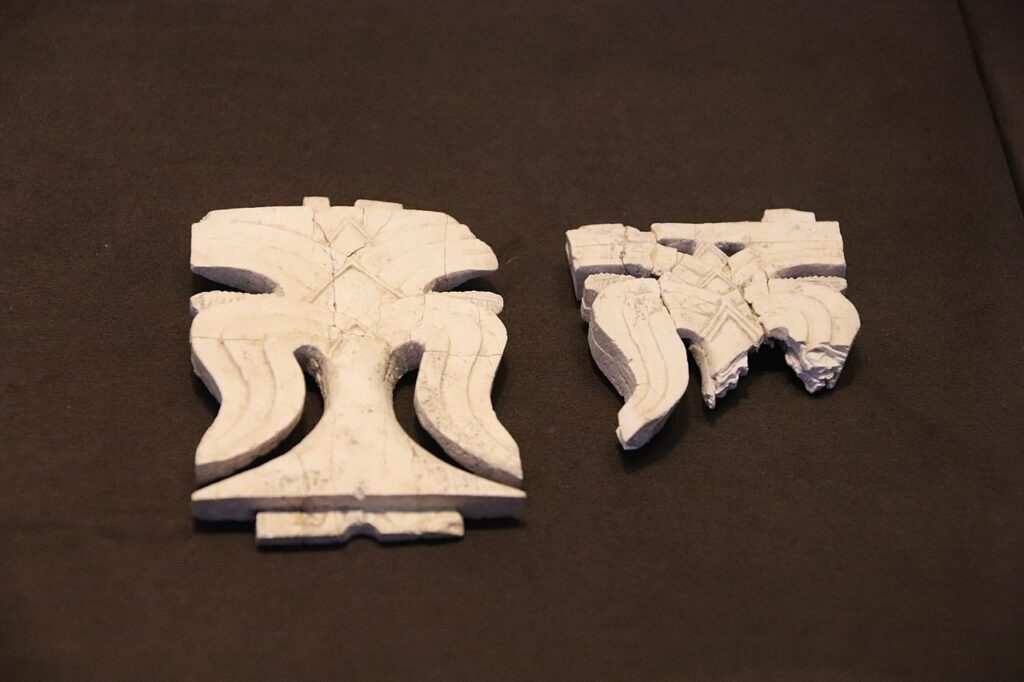

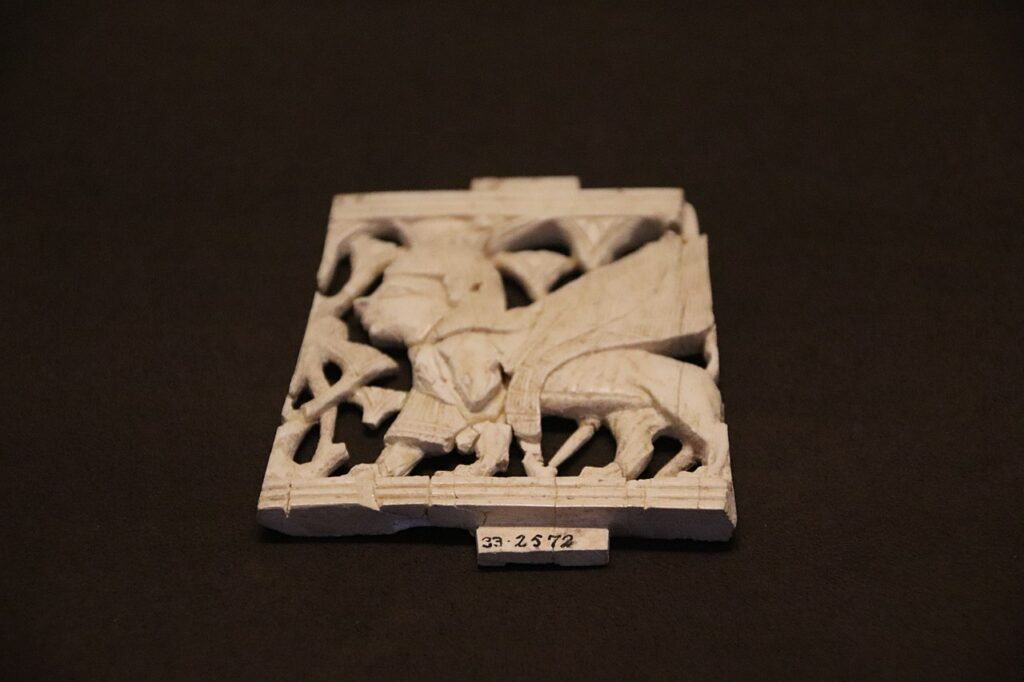

The many ivories found at the palace align with biblical descriptions of the “ivory house” built by Ahab (1 Kings 22:39) and the “beds of Ivory” in Amos’ prophecies during the reign of King Jeroboam II (Amos 6:4).

Examples of the Samaria Ivories, presented in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Samaria under the Jehu Dynasty (841-747 BCE)

Despite economic and military prosperity, opposition arose to the political and religious policies of the Omride kings. During Israel’s war against Aram-Damascus, Jehu, who was one of Israel’s generals, led a rebellion, killing King Jehoram and establishing a new dynasty. Even after the deposition of the Omrides, Assyrians continued to refer to Israel as the “House of Omri” or “Samerina,” highlighting Samaria’s centrality. Jeroboam II, the great-grandson of Jehu, ruled during a golden age, marked by Amos’ doom prophecies against the moral corruption of the Israelite elite.

Adjacent to the royal palace was a large warehouse building with Hebrew ostraca (“Samaria Ostraca”), documenting shipments of wine and oil to the king’s palace from Mount Ephraim. These ostraca are significant for studying the Hebrew language and script, as well as the administration and economy of Israel. The ostraca mostly note the names of the royal official and the shipment’s content, and often the name of the estate from which it arrived. The date of these ostraca is still discussed, but in recent years it has been suggested they are dated to the reign of Jeroboam II. Recently it was hypothesized they were linked to shipments of cultic offerings to a temple in Samaria.

The remains of the Israelite palace in Samaria.

Destruction of Israel and Samaria is an Assyrian and Babylonian district capital (747-539 BCE)

After the death of Jeroboam II, political chaos ensued, leading to Assyrian conquests and the eventual capture of Samaria. The city was not destroyed but transformed into an Assyrian administrative center, the “Samerina” province. With Assyria’s decline, King Josiah of Judah took over the territory, desecrating shrines. The Babylonians razed Jerusalem by 587 BCE. After the destruction of Jerusalem, Samaria and Judah maintained economic relations, as indicated by (Jeremiah 45:4-8). Archaeological findings in Samaria include pieces of an Assyrian stele linked to King Sargon II, an Assyrian cylinder seal, and a Babylonian clay tablet letter to a local governor named “Abi-Ahi.”

Persian province of Samaria (539-332 BCE)

Samaria remained an administrative center after the conquest of King Cyrus of Persia in 539 BCE with Sanballat the Horonite as governor. From the Persian period, a wide garden (50 x 45 m.) which surrounded the governor’s palace was excavated. The wealth of Samaria is portrayed in the archaeological findings: Athenian and Sidonian coins, 14 Aramaic inscriptions and a large quantity of pottery vessels, imported from the Aegean Sea. It is possible that Judah was under Samaria’s influence, which prompted the opposition of Samaria’s rulers to the reestablishment of Jerusalem’s walls during the time of Ezra and Nechemia. The scholar Hanan Eshel has reconstructed, using various historical sources, the list of rulers in Samaria: Sanballat I, Daliya, Shlomiah, Hananiah, Sanballat II and Yeshua/Yehoshua.

Hellenistic Samaria and John Hyrcanus’ conquest (332-63 BCE)

Shortly after Alexander’s conquest, the Samaritans assassinated the Greek general Andromachus. This brought Alexander’s wrath and the flight of many of Samaria’s residents. These were massacred by the Macedonian army in the cave in Wadi ed-Daliya. Following these events, Samaria became a Greek city and lost its status as an administrative to Neapolis (Shechem). Alexander’s successors established a large fortress with thick defensive walls, with a width of 4 m., and impressive towers. Samaria continued to flourish, and this is seen in thousands of imported wares found in the city.

One of Samaria’s classical era towers, photo taken by Ovedc – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52494195

John Hyrcanus, the ruler of Hasmonean Judah (134-104 BCE) led a military campaign in the Samarian highlands, and after a year-long siege who conquered the city and destroyed its walls. Samaria remained under Hasmonean rule until the Roman conquest by 63 BCE.

Roman period and Herod’s rule (63 BCE and afterwards)

During the Roman period, Samaria reached its all time peak and wealth, with major reconstruction under Gabinius (57-55 BCE), whose days saw the construction of a wall, residential quarters, a forum, and a basilica. King Herod expanded the city’s fortifications, established a stadium and theatre. He renamed the city “Sebastia” in honor of Roman Caesar Augustus (whose Greek name was “Sebastus”) and established the “Augusteum”, a temple dedicated to the Ceaser. Another temple dedicated to the goddess Kore, was apparently built on an earlier temple dedicated to the Egyptian gods Isis and Sarapsis. The city was a hub for celebrations, cult and ceremonies and gradually declined during the Byzantine era.

Its Greek name is preserved until this day in the nearby Palestinian village.

Remains of the Roman forum.

Biblical Hiking map

Sources:

Finkelstein, F. 2021. Notes on the Date and Function of the Samaria Ostraca. Israel Exploration Journal 71. 162-179. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27194659

Finkelstein, F. 2011. Observations on the Layout of Iron Age Samaria. Tel Aviv 38. 194-207. https://doi.org/10.1179/033443511×13099584885303

Franklin, N. 2004. Samaria: from the Bedrock to the Omride Palace. Levant 36. 189-202. https://doi.org/10.1179/lev.2004.36.1.189

Tappy, R. E. 2001. The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria, Volume 2: The Eight Century BCE. Harvard Semitic Studies 50.

Eshel, H. 1999. The Rulers of Samaria during the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BCE. Eretz Yisrael 26. 8-12. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23629878

Avigad, N. “Samaria”. From: Stern, E. (ed). 1992. The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land Vol. 4. 1300-1310ץ